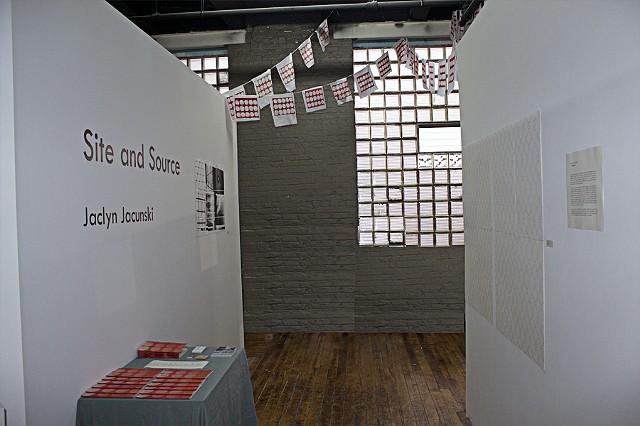

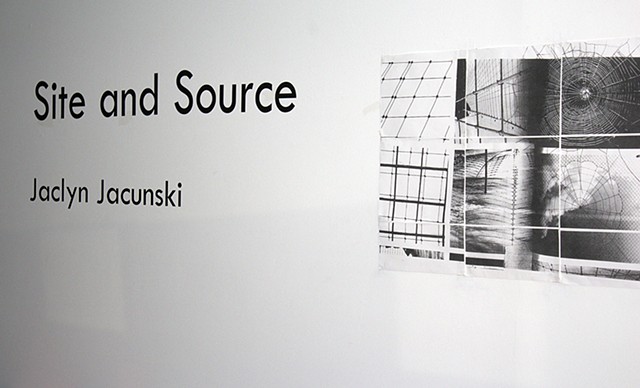

Site & Source, Spudnik Press 2013

Now is the Time: From Fence to Form

As Marxist art critic Ben Davis recently pointed out in his book 9.5 Theses on Art and Class, “there is no elegant fit between art and politics.” This age old lament is not lost on artists in Chicago. This beautiful, violent, emerging, waning, wealthy, broke, built, vacant, developing, vibrant city of contradictions is a complex place where artists are as engaged politically as they are anywhere else.

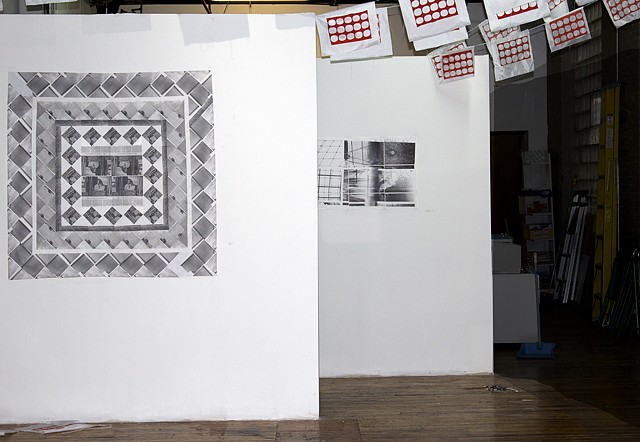

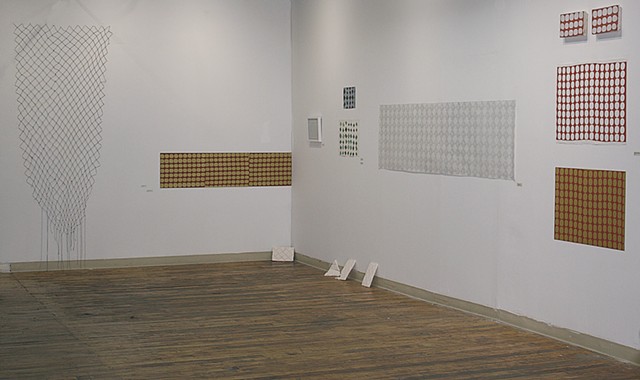

For works in her solo exhibition, Site and Source, Jaclyn Jacunski (she herself has a history with political activism) turned to activists past and present for inspiration—the omnipresent Martin Luther King and Detroit’s Grace Lee Boggs—and then to Chicago’s urban landscape for her materials, gathering debris, fencing and found objects from an abandoned lot near her home on the northwest side. Fences in particular are a consistent presence in her drawings, prints and installations graphically and physically. In this exhibition, each individual component is a deliberate extension of or departure from the next, a network of art objects that as investigations utilize text, color and pattern to reduce the fence itself as image and object mostly into a series of abstractions.

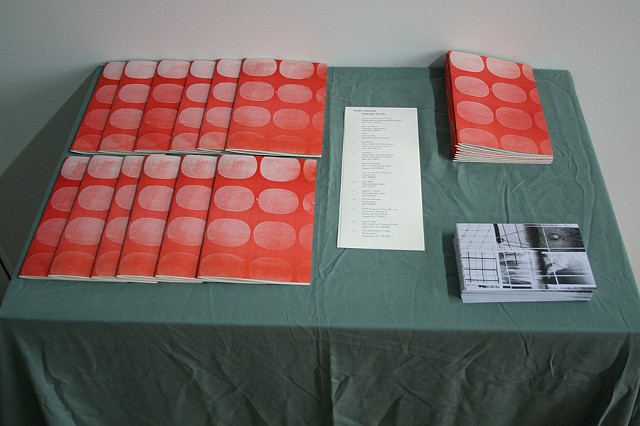

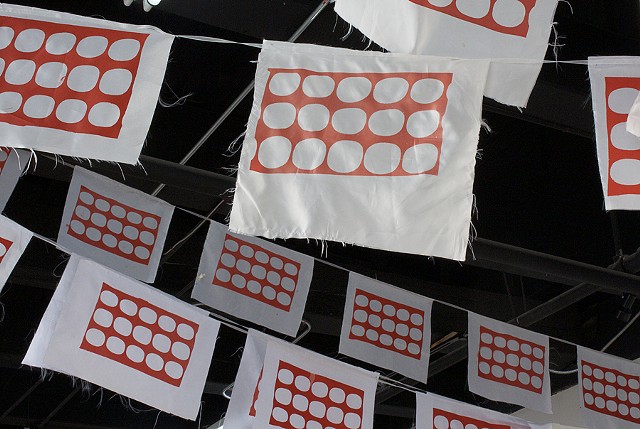

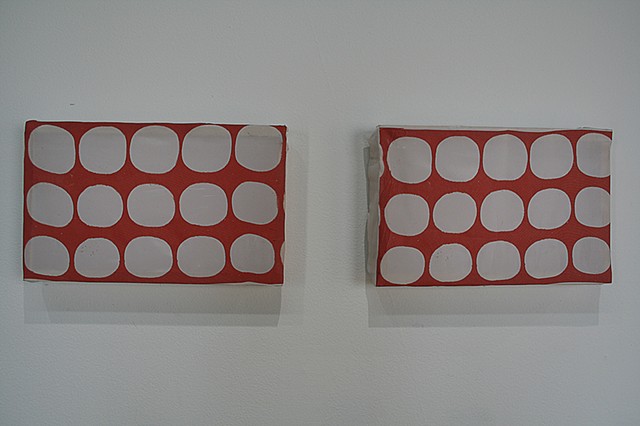

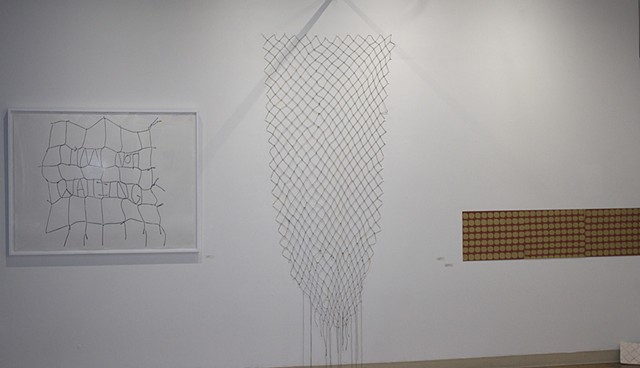

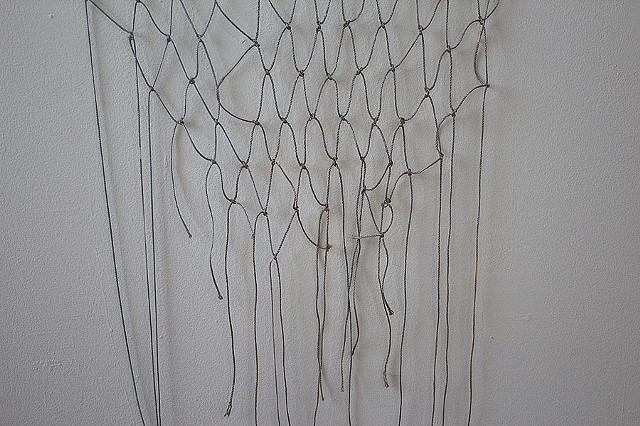

Poetics and Politics of Fences, a series of pressure prints, each with an allover distribution of subtly imperfect gold or white ovals on a red background, are presented both as works on paper and also prints wrapped onto small canvases. At first glance they seem to nod nonchalantly towards the history of modernist abstraction or decorative arts. Upon closer inspection and taken in context, however, one realizes they are impressions of the fiery red plastic fencing often found on construction sites. Repeated onto a site-specific installation of white Buddhist prayer flags that gently hang over the Annex (the gallery doubles as a literary workspace), the oval pattern cleverly shapeshifts to resemble cinder blocks. In another foray into pattern, Untitled 1 & 2 (screen), bits of green tarp are fragmented into a cascading arrangement, falling netlike on a picture plane-as-void. What can be made of such abstractions? Why should these compositions emerge out of empty lots that are as real as they are dirty and symbolic of disorder? Perhaps, by asserting a new and purposeful visual field of possibility for the doldrums materials of fencing, Jacunski generatively carves out a new spatial imaginary for the everyday. As philosopher Jacques Ranciere provocatively suggests, in art the very picture plane or surface can become an emancipatory model for the real world: “…by drawing lines, arranging words or distributing surfaces, one also designs divisions of communal space. It is the way in which, by assembling words or forms, people define not merely various forms of art, but certain configurations of what can be seen and what can be thought, certain forms of inhabiting the material world.”

Emancipatory models aside, let’s consider the fence itself and what it does to social space in the first place. Sociologist Bruno Latour might assert that the fence as object contains its own script for social relations. In the essay “How to do Words with Things” Latour describes the incredible influence of one simple key in the activities and relations of a tenant, landlord, thief and delivery person, among others: “From being a simple tool, the key assumes all the dignity of a mediator, a social actor, an agent, an active being.” Likewise a fence is a barrier to entry, meant to demarcate zones of ownership or membership. It begs to be obeyed or defied, climbed, defaced or backed away from. Interestingly, a fence can also be a viewing device—its chain links or iron slats serve as viewfinders, framing “the other’s” territory and slicing its contents into the very shapes and forms that Jacunski captures and reorients spatially in her prints and drawings.

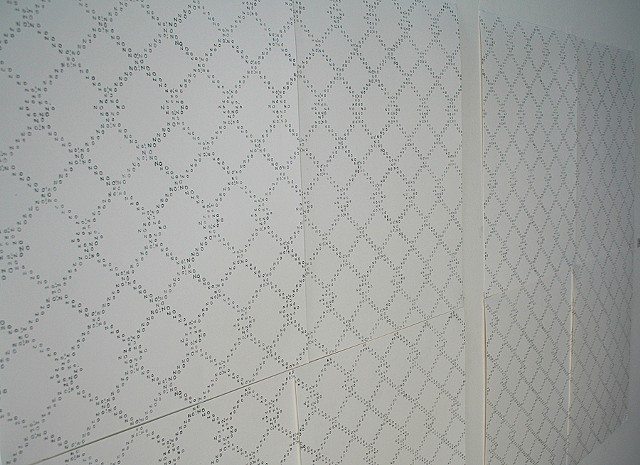

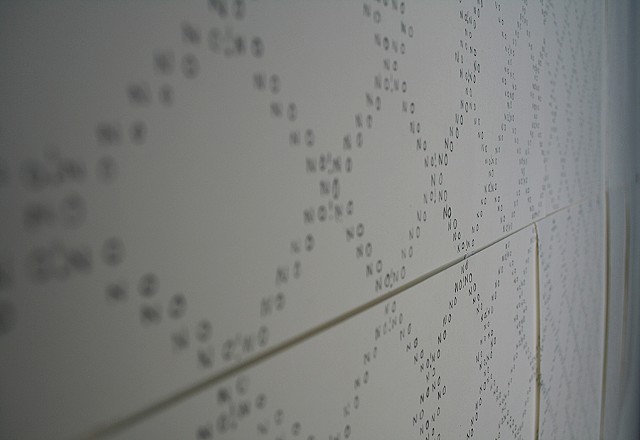

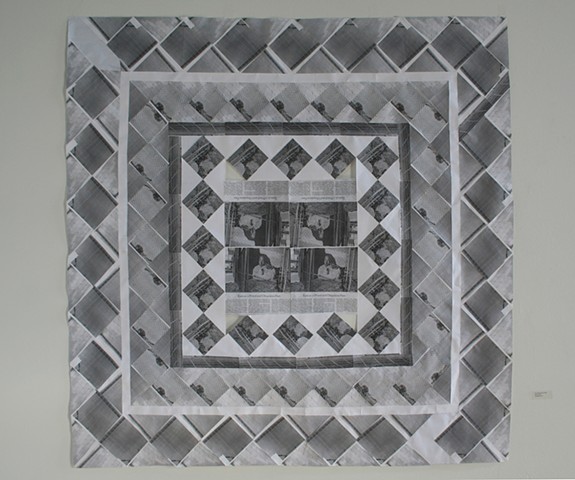

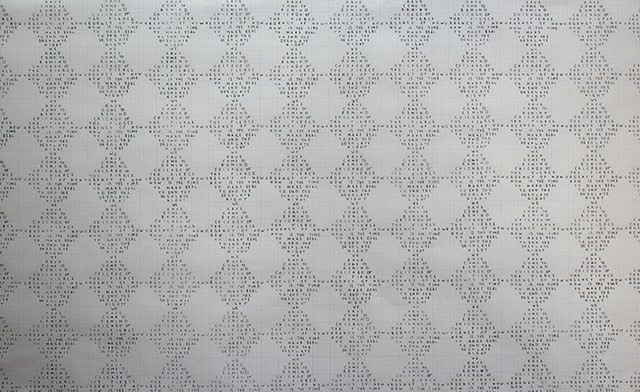

Jacunski’s works are not always devoid of representational human presence or activity—through hand lettering in some works on paper, it is in the appearance hypergraphic text that her voice as an activist and educator are manifest. In the piece NO! , that carefully written word in graphite over and over again in the pattern of a fence makes visible a durational or, as she suggests, “parochial” effort to vocalize and mobilize change: the utterance is “NO!” but what was the protest for? In the drawing Remind Chicago, however, she turns a corner from ambiguity to historical specificity: she copies collaged language from several historic Martin Luther King speeches over and over: “WE HAVE COME TO REMIND CHICAGO OF THE FIERCE URGENCY OF NOW / NOW IS THE TIME TO MAKE REAL / TO END THE DESOLATE NIGHT.” Here also, repetition and the activity of copying, again in a fence-like diamond pattern, points to the cyclical, repetitive nature of protest, though this time it is in the spirit of reverence in addition to remembrance. And importantly, as the “parochial” activity of a student, hand copying in pencil alludes to the politics of power, hierarchy and pedagogy that still characterize the experience of activism for many.

Artist Teddy Cruz recently pointed out that as artists “reorient” their work towards “other sites of research and intervention … the most relevant practices and projects forwarding the socio-economic sustainability will emerge not from sites of abundance but from sites of scarcity”. For Jacunski, her “site of scarcity” is just one of over 20,000 vacant lots that exist on Chicago’s near west and south sides. Working in a brilliant legacy of public works for which Chicago artists—such as Daniel Joseph Martinez, Iñigo Manglano-Ovalle and Juan Angel Chavez— have addressed the fence as sociologically coded infrastructure on sparse, empty grounds, Jacunski draws out of negative space forms from which emerge poetic considerations of the urban landscape relative to economics, politics and, most importantly, the individual subject.

essay by Jessica Cochran

Ben Davis. 9.5 Theses on Art and Class (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2013: 48).

Jacques Ranciere. The Future of the Image (London: Verso, 2003: 100).

Bruno Latour. “How to do Words with Things,” in Ecstatic Alphabets/Heaps of Language, Stuart Bailey, Angie Keefer and David Reinfurt, ed. (New York: Sternberg Press, 2012: 18).

Teddy Cruz. “Democratizing Urbanization and the Search for a New Civic Imagination,” in Living as Form: Socially Engaged Art from 1991-2011, Nato Thompson, ed. (New York: Creative Time Books, 2012: 61).